IAMCR members, Colin Chasi, Nyasha Mboti and Viola Milton from South Africa are co-sponsoring an IAMCR preconference, "Towards Participation Studies" in association with the 2015 conference in Montreal. The pre-conference will take place on 11 July 2015 and "is envisaged to be an enabling founding moment in creating and re-creating unapologetic modes of thought and practices grounded in African worlds."

-

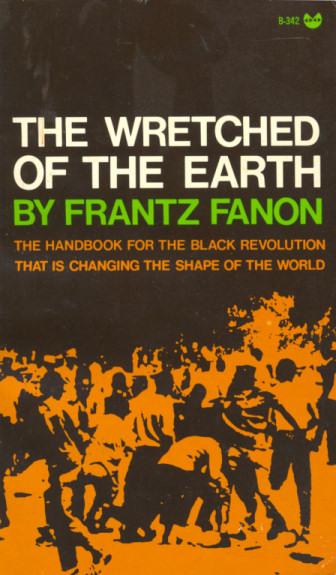

In The Wretched of the Earth, radical philosopher Frantz Fanon says “...it is very true that we need a model, and that we want blueprints and examples.” (p.312). He further remarks:

Let us reconsider the question of mankind. Let us reconsider the question of cerebral reality and of the cerebral mass of all humanity, whose connections must be increased, whose channels must be diversified and whose messages must be re-humanized. (p.314)

These remarks are critical to the fields of communication, media and cultural studies. The way we think about, research and teach communication/media/culture in African universities has not re-emerged, in any substantial sense, from the shadows of received theories. If anything, our practice has seemed to involve less and less reconsideration of the “cerebral mass of all humanity”. We still think about, research and teach communication/media/culture through innovative adaptation of received wisdoms. This asymmetry, while making us expert adaptors, has not necessarily made us better theorists. It is important to ask, once more: how should locally valid theories emerge? We propose that, in particular, among many possible plural emphases, one emphasis stands out: a study of “participation”.

We are proposing a panel to discuss possibilities for the emergence of “Participation Studies”.

The "participation studies approach" is proposed as a counter-weight to conventional communication, cultural studies and media studies frameworks of enquiry. The main objection to conventional frameworks is not that such theories are non-African. Rather, the objection is that such theories do not always adequately march in step with qualitative transformations in the everyday lives and lived realities of Africans. At base, this is a question of relevance. This is one criterion by which a theory is acceptable as "African".

Communication/cultural studies/media scholars in Africa have tended to locate themselves in trajectories of conceptual mobility that leverage, mobilise and re-create northern codes of communication language and theory. These scholars re-process disciplinary jargon within a de-territorialised, over-imitated discursive Western conceptual space that engenders epistemic prescriptions and obscures the experientiality of the local and the ordinary. The resulting pitfall in is the preoccupation with literature review type practices of quoting and summarising previous scholarship with little fresh input. As theorists we have so far failed to adequately constitute ourselves as organic intellectuals marching in step with local formations and transformations. The consequences have been far-reaching: the building of theory rooted in African experiences has remained a peripheral subject, attracting few takers. Although flows of knowledge are by no means unidirectional, the Northern centre continues to exert important centripetal force. Africa, then, simply provides a convenient backdrop for the popularisation of Northern-based approaches. Ordinary Africans’ everyday vocation as searchers and questioners, their vocation as feeling, thinking beings who actively fill things with meaning, is undervalued.

By participation, however, we do not refer to the delexicalised concept peddled by the global “participation industry”. This global industry is sustained by the very same institutions that take wealth from the poor to give to the rich. It uses the “grassroots” as a gate-pass to imbedding in ordinary people’s lives, re-creating silences in the guise of giving voice, and creating masters and servants under the illusion of “involving”. Rather, we intend to rescue the “participation” from this sinister over-use, relexicalising it in the service of a larger “Critical Participation Studies” project. The papers and discussions presented in this panel define “participation” in its relexicalised form and outline some of the salient theoretical aspects of a new critical “Participation Studies”. We argue that overcoming the multiple il-legacies of colonial thought and apartheid thought requires, in addition to whatever critical decolonial projects African scholars have been involved in, critical qualitative transformations in the nature of how we theorise, think and act.

The common, normalised practice of repurposing and over-imitating theories and methodologies developed elsewhere to explain and address problems facing African societies comes with its inherent unwitting damages, losses and deficiencies such as re-enacting domination and dehumanisation through the very same forms meant to critique and resist them. This one emphasis on “participation” has some potential to facilitate debate about locally valid theory.

Participation speaks to the lives of ordinary Africans, how they participate in shaping local realities and lived conditions. When communities of actors continuously alter everyday worlds by repeatedly filling them with their own meanings, as opposed to the borrowed, imposed or unsought meanings of others, participation occurs. Through participation, people move from being passive receivers and consumers to questioners, knowers, producers and sharers of ideas and initiators of social change and local development. Seen this way, participation is a form of crystallisation that reflects where Africans have come from, where they are in the world, and their individual and collective aspirations. This state of affairs describes what Frantz Fanon (1963) has called a “national culture”, defined as “the all-embracing crystallization of the innermost hopes of the whole people” (1963: 148).

This preconference panel proposes a fluid approach that combines, is within, and goes beyond communication studies/cultural studies/media studies frameworks that systematically studies such qualitative transformations: the participation studies approach. Participation studies are envisaged as the study of how Africans go about qualitatively, performatively, and trans/formatively shaping their everyday worlds. Participation studies throws light on the visible and invisible acts and practices that result in closed worlds and limit ownership to a few. It links together visible and invisible acts and practices of opening up closed worlds and winning ownership for all on behalf of national cultures. The participation studies approach focuses on building critical corpora of African scholarship and theory that routinely places the everyday worlds, needs and uses of Africans first. The papers and discussions in this panel propose to develop and defend a novel approach of communication/culture/media that adequately fulfils the condition and principle of marching-in-step with African experiences and worlds. We are of the view that conventional communication/cultural studies/media studies field(s) in general lacks such an approach.

Are our emphases the same as those of so-called development communication and participatory communication? Actually, no. We believe that the frameworks adopted by development communication and participatory communication mostly reflect the continuing infatuation with imbedding in communities for no other purpose than to find a “grassroots” way of telling people what is good for them, and calling this “participation” or participatory communication. We believe that these practices and theories generally fail in Africa (and elsewhere in the global south) largely because they are predicated on practices that legitimate stolen wealth.

Participation studies is not envisaged as a response or critique to Western frameworks. Africans are mostly tired of responding to the West. In this regards, we take Toni Morrison’s advice:

The function, the very serious function of racism is distraction. It keeps you from doing your work. It keeps you explaining, over and over again, your reason for being. Somebody says you have no language and you spend twenty years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientists working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. Somebody says you have no kingdoms, so you dredge that up. None of this is necessary. There will always be one more thing.

The idea of a critical participation studies is thus not obsessed with the validating business of finding grounds for its needfulness. Rather, it is about founding conversations. The meeting is envisaged to be an enabling founding moment in creating and re-creating unapologetic modes of thought and practices grounded in African worlds. Entry points include, but are not be limited to, the following twenty emphases:

- Rethinking/redefining “participation”

- Naming and re-naming “participation”

- Defining “participation studies”

- Theorising “participation studies”

- Participation and being human

- Histories of participation

- Knowledges of participation

- Participation and the everyday

- Participation and the ordinary

- Participation practice(s)

- Participation and power

- Participation and justice

- Participation and social justice

- Participation and love

- Participation and culture

- Participation and communication

- Participation and freedom

- Participation and identity

- Whose participation?

- Why participation?

A journal special issue and book project are envisaged, as are follow-up conference panels and pre-conferences in 2016 and 2017.

List of Confirmed Panellists:

- Prof. Colin Chasi (South Africa/Zimbabwe)

- Dr. Nyasha Mboti (South Africa/Zimbabwe)

- Prof. Viola Milton (South Africa)

- Dr. Winston Mano (UK/Zimbabwe)

- Dr. Bruce Mutsvairo (UK/Zimbabwe)

- Dr. Vicensia Shule (Tanzania)

- Dr. Dominica Dipio (Uganda)

- Prof. Martin Mhando (Tanzania/Australia)

- Prof. Onookome Okome (Nigeria/Canada)

- Dr. Abraham Mulwo (Kenya)

- Dr. Levy Obonyo (Kenya)

- Prof. Ntongela Masilela (South Africa/Thailand)

- Prof. Handel Kashope Wright (Sierra Leone/Canada)

- Prof. Moradewun Adejunmobi (Nigeria/US)

- Prof. Thomas Tufte (Denmark)